| |

|

Chapter 2: The Digital Representation of Sound,

Part Two: Playing by the Numbers

Section 2.6: Digital Copying

|

| |

One of the most

important things about digital audio is the ability, theoretically, to

make perfect copies. Since all we’re storing are lists of numbers,

it shouldn’t be too hard to rewrite them somewhere else without error.

This means that unlike, for example, photocopying a photocopy, there is

no information loss in the transfer of data from one copy to another,

nor is there any noise added. Noise, in this context, is any information

that is added by the imperfections of the recording or playback technology.

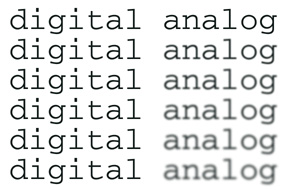

Figure 2.15 Each generation of analog copying is a little noisier than the last. Digital copies are (generally!) perfect, or noiseless.

|

|

Xtra bit 2.2

The peanut butter conundrum

|

Not-So-Perfect Copying

What does perfect copying really mean? In the good old days, if you copied your favorite LP vinyl (remember those?) onto cassette and gave it to your buddy, you knew that your original sounded better than your buddy’s copy. He knew the same: if he made a copy for his buddy, it would be even worse (these copies are called generations). It was like the children’s game of telephone:

"My cousin once saw a Madonna concert!"

"My cousin Vince saw Madonna’s monster!"

"My mother Vince sat onna mobster!"

"My mother winces when she eats lobster!"

|

|

|

Applet 2.5

Melody copier

|

Start with a simple tune and set a noise parameter that determines how bad the next copy of the file will be. The melody degrades over time.

Note that when we use the term degrade, we are giving a purely technical description, not an aesthetic one. The melodies don’t necessarily get worse, they just get further from the original.

|

|

|

Xtra bit 2.3

Errors in digital copying: parity

|

The noise added to successive generations blurs the detail of the original. But we still try to reinterpret the new, blurred message in a way that makes sense to us. In audio, this blurring of detail usually manifests itself as a loss of high-frequency information (in some sense, sonic detail) as well as an addition of the noise of the transmission mechanism itself (hiss, hum, rumble, etc.).

|

|

|

Soundfile 2.4

Our rendition of Alvin Lucier’s "I am Sitting in a Room"

|

Alvin Lucier’s classic electronic work, "I Am Sitting in a Room," "redone" with our own text.

"This is a cheap imitation of a great and classic work of electronic music by the composer Alvin Lucier. You can easily hear the degradations of the copied sound; this was part of the composer’s idea for this composition."

We strongly encourage all of you to listen to the original, which is a beautiful, innovative work.

|

|

| |

Is It Real, or Is It...?

Digital sound technology changes this copying situation entirely and raises some new and interesting questions. What’s the original, and what’s the copy?

When we copy a CD to some other digital medium (like our hard drive), all we’re doing is copying a list of numbers, and there’s no reason to expect that any, or significantly many, errors will be incurred. That means the copy of the president’s speech that we sample for our web site contains the same data—is the same signal—as the original. There’s no way to trace where the original came from, and in a sense no way to know who owns it (if anybody does).

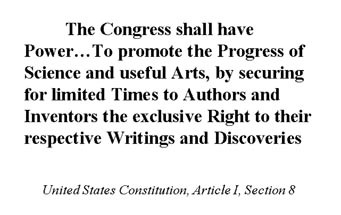

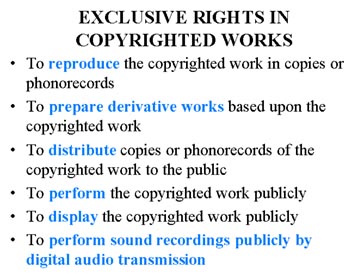

This makes questions of copyright and royalties, and the more general issue of intellectual property, complicated to say the least, and has become, through the musical technique of sampling (as in rap, techno, and other musical styles), an important new area of technological, aesthetic, and legal research.

"If creativity is a field, copyright is the fence."

—John Oswald

In the mid-1980s, composer John Oswald made a famous CD in which

every track was an electronic transformation, in some unique way, of

existing, copyrighted material. This controversial CD was eventually

litigated out of existence, largely on the basis of its Michael Jackson

track (called "Dab").

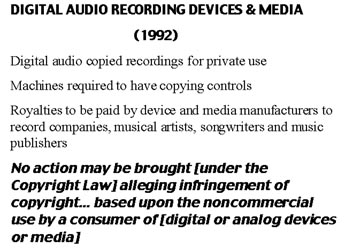

Digital copying has produced a crisis in the commercial music world, as anyone who has downloaded music from the internet knows. The government, the commercial music industry, and even organizations like BMI (Broadcast Music Inc.) and ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers), which distribute royalties to composers and artists, are struggling with the law and the technology, and the two are forever out of synch (guess who's ahead!). Things change every day, but one thing never changes-technology moves faster than our society's ability to deal with it legally and ethically. Of course, that makes things interesting.

Figure 2.16

Figure 2.17

|

|

Soundfile 2.5

Pretender, from John Oswald’s Plunderphonics

|

In Pretender,

John Oswald gradually changes the pitch and speed of Dolly Parton’s

version of the song "The Great Pretender" in a wry and musically

beautiful commentary on gender, intellectual property, and sound itself.

Figure 2.18

Figure 2.19

|

|

Soundfile 2.6(a)

Original

Soundfile 2.6(b)

Degraded

Soundfile 2.7

David Mahler

Xtra bit 2.4

Digital watermarking

|

Soundfiles 2.6(a) and 2.6(b) show an analog copy that was

made over and over again, exemplifying how the signal degrades to noise

after numerous copies. Soundfile 2.6(a) is the original digital file;

Soundfile 2.6(b) is the copied analog file. Note that unlike the example

in Soundfile 2.4, where we tried to re-create a famous piece by Alvin

Lucier, this example doesn’t involve the acoustics of space, just

the noise of electronics, tape to tape.

|

Figure 2.20 David Mahler

|

Sampling, and using pre-existing materials, can be a lot of fun and artistically interesting. Soundfile 2.7 is an excerpt from David Mahler’s composition "Singing in the Style of The Voice of the Poet." This is a playful work that in some ways parodies text-sound composition, radio interviewing, and electronic music by using its own techniques. In this example, Mahler makes a joke of the fact that when speech is played backward, it sounds like "Swedish," and he combines that effect (backward talking) with composer Ingram Marshall’s talking about his interest in Swedish text-sound composers.

The entire composition can be heard on David Mahler’s CD The Voice of the Poet; Works on Tape 1972–1986, on Artifact Recordings.

|

©Burk/Polansky/Repetto/Roberts/Rockmore. All rights reserved.